Harmen Beukers (1945–2020), in memoriam

by Harold J. Cook

I came to know Harmen Beukers as an energetic, courteous, sociable, and inquisitive scholar, someone holding to the ambition of bridging the alpha and beta worlds of the modern academy. Both sides have their blind spots, but he was eager to mark guideposts raised in the past so that we could recognize them when finding our own direction. He mentored me and many other students, scholars, and friends with a direct, no-nonsense care and friendship. He was a natural supporter of the institutions that make our lives possible, mobilizing his local network to set up a faculty club or in later years happily putting on an academic gown to fill out many academic boards for the dignity of a Ph.D. defense at his beloved Leiden University. Events he helped to organize might be for the public – like the annual open-house for the anatomical specimens in the university’s medical collections – but he hoped they would help to inspire knowledge more than elicit bewildering wonder. His kind of Dutch gentleman, I discovered, was both private and cosmopolitan, critical and exacting, seeking to investigate the facts with care and diligence; but Harm also had an open sense of humor and a love of being on the move, often venturing onto new ground by taking on fresh challenges, not least learning Japanese when no longer in his youth. He was a colleague and a teacher, and to at least some of us, a friend.

We first met on a cold a rainy day in January 1987, when he offered me a desk in his office for a period of research. Several months earlier I had made the acquaintance of Harm’s chief, Dr and Prof A. M. Luyendijk-Elshout (and Eddy Houwaart and Mart van Lieburg) at a conference in Cambridge organized by Andrew Wear and Andrew Cunningham, and when she learned of my ambition to broaden my horizons by embarking on the study Dutch medicine in the 17th century she offered to help. Antonie Luyendijk headed a small history of medicine department within the medical school at Leiden in which Harm had been her junior colleague since 1981. Having with her help arranged to spend a month in a small room in the university’s guest house (after which I moved to a room in a former nursing home a bike-ride away), and having signed up for a local Dutch language course (having gotten my feet wet in an introductory course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison), I paid a call on Antonie, who introduced me to Harm. I later learned that Harm had been a very talented Ph.D. in medical biochemistry who had studied codicology and paleography with the medievalist Peter Gumbert before turning to medical history under Tonny’s guidance.

Harm kindly cleared some desk space in the corner of his office and asked what brought me there. My plan was to learn about how the Dutch libraries and archives worked by tracking down what I could about the early life of Joannes Groenevelt, whose track I had come across in London. Harm explained that he had been studying the iatrochemist and mechanist François dela Boë, Sylvius and his students, among whom was Groenevelt. For a moment I worried about the possible frictions of an academic rivalry. But then in an act of enormous generosity Harm set in front of me several cardboard boxes full of his alphabetized notecards on all the students who had matriculated in medicine at Leiden in the 17th century with information he had collected about them from published and archival sources, and told me I should take down any and all of the information for my own use. The only rule was that as long as I was in his office we would speak only in Dutch. It was a good rule, and before I left early in the summer I began to pride myself on beginning to grasp his tongue when on occasion he would ask me to leave when he answered an important phone call.

Harm took me in hand in other ways, too. He brought me into his home, where Gemma Cottaar-Beukers’ warmth and Saskia’s curiosity made me very welcome. When I returned with Faye to Leiden in 1989-90 for a more extended period of research – the year the Berlin Wall came down – Harm, Gemmie, and Saskia became our friends as Harm continued his mentoring. When Saskia studied for a year in a US high school they of course visited us, too. Antonie was also hospitable and made time to take me for a quick day-tour of North Holland. But Harm reintroduced me to Mart van Lieburg and to colleagues like Wim Mulder, who oversaw Leiden’s anatomical collections, as well as to other historians of medicine and pharmacy like Annette Bierman and Hilary Marland (who was then working in Mart’s group in Rotterdam). Also in the Leiden group at the time was A.H.M. (Toon) Kerkhoff, a physician who had taken his doctorate in medical history with Daniel de Moulin in Nijmegen in 1976 and who continued to study history when he could while being in charge of the local GGD. Since Toon had some days off at the time he helped me find a simple staat fiets and brought me, and later Faye, into the orbit of his warm family, too.

But it was Harm who became my chief guide to the Dutch academic and historical world. From the beginning, he brought me along to academic lectures and meetings even when I understood little. Through Harm I learned about the larger world of the history of medicine, science, and technology throughout the low countries – Harm would later hold the Sarton Chair in 1998-99 – obtained an invitation to visit the history of science department in Utrecht, and discovered GEWINA. He helped me with Dutch paleography. The Boerhaave Museum and its library were getting ready for a move to new quarters, but Antonie and Harm enabled some access to the collection, and they arranged for me to have a pass to the university’s library. Most importantly, when we had a chance to talk Harm tamped down my rush to quick conclusions, corrected my mistakes and misapprehensions, and pointed me to other literatures. When I mentioned that one of Groenevelt’s friends was someone named Willem ten Rhijne, who had gone off to Japan, his finger went up, and he required me to look into him, which began to expand my geographical horizons much further. He was, in effect, my supervisor for a kind of habilitationsschrift that became my second book.

From 1980 to about 1987 Prof Beukers published important research on Sylvius and iatrochemistry in the 17th century and related subjects, much of it in GEWINA’s Tijdschrift. His article on “Clinical teaching in Leiden from its beginning until the end of the Eighteenth Century” made a significant impact on the history of medical education (it appeared in a volume he co-edited by J. Moll, Clinical Teaching, Past and Present, Rodopi, 1987). When he followed Prof Luyendijk to the chair of the history of medicine, in 1989, his oration was a passionate and erudite plea to his colleagues – including those in the medical faculty – to keep faith with the traditions of learning that had been fundamental to the establishment of the university in the first place: Terug naar de wortels. When he taught, medical students responded warmly to his learning and his message, and even the dean agreed that the Institute Biology Leiden should name its laboratory after Sylvius. When budget cuts in the medical school eventually began the process of closing the program in history of medicine, in 2007 the university appointed Prof Beukers the Scaliger Professor, enabling him to establish a center in the university library, with fellowships and PhD students, for studies using its special collections, in which capacity he continued to mentor a new generation.

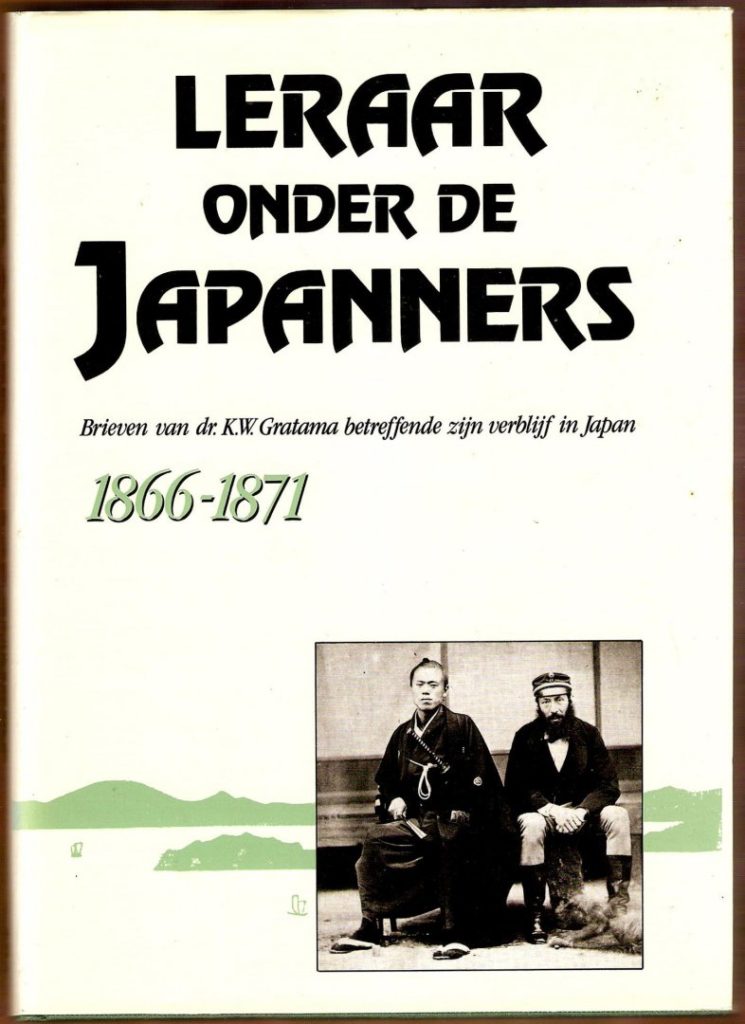

But Harm also became deeply immersed in the study of Dutch-Japanese medical relations, which became the focus of most of his later work, and he also began to spend time teaching there. Early in the 1980s he had been invited to Japan to participate in the annual history of medicine conference organized by Teizo Ogawa (Harm’s paper, “Medical Education in the Netherlands in the Nineteenth Century,” was published in a volume edited by Teizo Ogawa in 1983). He began conversations with Prof Leonard Blussé and other scholars of Asia at Leiden, in 1987 co-editing with Blussé and R. Eggink a study of Leraar Onder De Japanners: Brieven Van Dr. K.W. Gratama Betreffende zijn Verblijf in Japan, 1866-1871 (De Bataafsche Leeuw). About that time Harm began studying Japanese, and he became engaged with groups aiming to further good relations between the two countries. After the death of Gemmie in the later 1990s, he spent more time in Japan and married Myumi, who along with his daughter Saskia survives him.

As our responsibilities grew and our academic paths diverged over the years we did not often see one another, although it was a pleasure when we did. But I know that I am not the only person who was lifted by the generosity and critical erudition of Harm Beukers. People like himself may not be recognized for changing the world, but they make a difference, one person at a time. He kept the faith. May he rest in peace.

In memoriam Harm Beukers

R.Van Hee

Als mede-hoofdredacteur, samen met Harm, van het tijdschrift GdG (Geschiedenis der Geneeskunde) van 1993 tot 2011, heb ik Harm gekend als een erudiete persoonlijkheid, een joviaal en tegelijkertijd voornaam academicus, geleerd en belezen, doch evenzeer een levensgenieter.

Ik zal onze bijeenkomsten in Antwerpen, zowel bij mij thuis als bij de uitgeverij Garant, blijven herinneren.

Een groot man, voor mij een ware vriend.

Hij ruste in vrede.

Bob.